Martin's DSA Newsletter #7

Jul 09, 2025

Finally! The DSA newsletter is back. The last couple of months were very hectic on many fronts. I think if you read the newsletter, you will understand. So let's get right into it.

The seventh edition summarises the long period from October 2024 to June 2025. It covers the first publication of risk management dossiers, new EC investigations into adult sites, acceptance of commitments by AliExpress, upcoming guidance on minors, new rules for data access for researchers, codes of conduct on disinformation and hate speech, news about ODS bodies, several pending court cases on the national level, and much more.

Platform Regulation Academy

As usual, let me start with a personal update. As many of you know, I have been training on the DSA for the better part of two years. Based on the received feedback from many of you, I am taking this activity to a new level. I have co-founded the Platform Regulation Academy, an organisation whose mission is to educate professionals and stakeholders on the questions of platform accountability. My reason is fairly simple. I love research. And remain an academic through and through. But since only people can change the status quo, PlatReg Academy is my way how reach professionals and stakeholders and teach them about the law and practice of platform regulations. This is why this newsletter is now being sent from the Academy's mailing system.

You can expect an expansion of the course offering beyond the DSA Specialist Masterclass (BTW, readers have a special summer offer: 30 % off until 31.8.2025). The Academy will soon offer the EU Platform Regulation Compass, a general course that will teach the basics of the DSA, along with other platform-relevant parts of EU law, such as the AI Act, DMA, EMFA, AVSMD, UPCD, GPSR, CDSMD, and P2BR. If you want to get notified, just let us know here.

After offering many trainings for organisations, the PlatReg Academy will also offer hybrid training that consists of pre-recorded courses coupled with live instruction in local languages (e.g., expect an Italian live course in February 2026). If you are interested to learn more, sign up here. And no, I will not be butchering Italian or Spanish; lecturers will be all local experts, but I will help them with content delivery methods and substance. I always welcome tips on what local languages would be of interest to you.

Finally, I am in talks with Oxford University Press to release my DSA book, Principles of the Digital Services Act, as open access. If everything goes well, maybe this could happen as soon as mid-2026.

Risk Management Dossiers

In November 2024, the companies published the first set of risk management dossiers. These dossiers include systemic risk assessment and mitigation reports (SRAMs), audits, and audit implementation reports. Alexander Hohlfeld did everyone a huge favour by tracking them all down. His list is here. The number of pages to digest is truly enormous. Even after months, I have managed to read only a subset of the documents. However, I am aware of several groups that are systematically coding the materials, so we might read their analysis soon.

In January, I held a conversation at LSE with Agne Kaarlep (Tremau), Curtis Barnes (ex-Delloite), and Prof. Lorna Woods (University of Essex) about these dossiers. The video recording is below.

|

There is much to be said about these first attempts to comply with the DSA's risk management framework. First, while a lot of effort has been put into these documents, they inevitably disappoint everyone who expected that companies would present how they think about risks posed by the design of their services. From the trio of 'design', 'functioning' and 'use' of the VLOP/VLOSE services, the documents mostly focus on 'use' by others, and some governance-related issues.

In Rene DiResta's triangle of algorithms, influencers, and crowds, the focus of these documents is largely on crowds and less on incentives for influential content creators and/or design features of services. Sometimes it also seems as if the design was treated only as a control for a risk, but less as a source of the risk itself. Going forward, one would expect that the design of services, including that of recommender systems, their defaults, features, and rewards schemes for content creators, be scrutinised as risk factors as much as potential risk mitigation strategies.

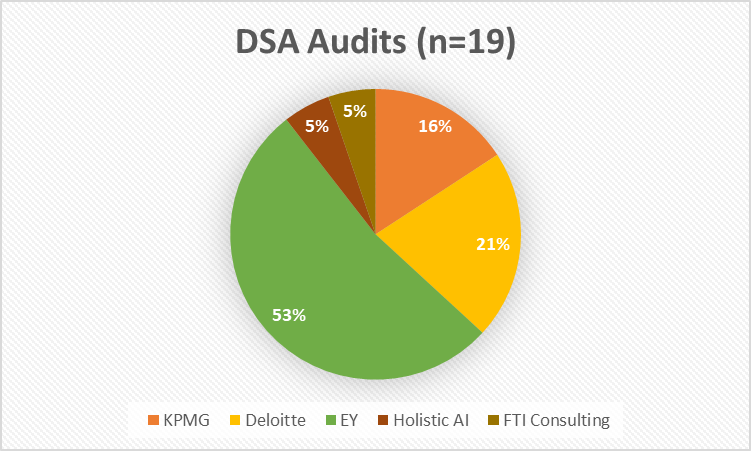

Our LSE event discussed the role of audits. Industry insiders emphasised that we have to read the reports as regulatory compliance reports, and thus not as something that is primarily drafted for an average citizen. Be it as it may, despite the concentration of auditing services (see the chart below), we see a plethora of different methods being used.

Taylor Annabell (Utrecht University) recently published a great deep dive into these documents, focusing on Article 26(2) compliance. Exactly because her focus is so narrow, she can nicely show that there is a lack of consistency in the basic methods of investigation for the purposes of auditing. Taylor concludes:

Across the eight assessments, we see wide variation in how the obligation is interpreted, the rigor with which assessments were conducted, the kinds of evidence auditors relied on, and the procedures used to assess compliance. These inconsistencies make it difficult to compare outcomes across platforms and raise questions about what standards, if any, are guiding the process.

When it comes to the functionality for disclosing commercial content, the uniformly positive conclusions by auditors are particularly troubling. Our previous research finds that self-disclosure mechanisms on platforms like Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, and YouTube fall short due to their (in)accessibility and (in)visibility. And yet, auditors still deemed these systems compliant. In doing so, the reports effectively legitimize a model in which platforms are free to offload responsibility for legal compliance onto influencers, while failing to ensure that disclosure functionality actually works in alignment with consumer protection law.

The documents also show that follow-ups to audits by companies can actually be very helpful. The problem, however, is that auditors so far often only work with self-imposed benchmarks of companies. The regulators can insert themselves into the conversation between auditors and regualtees by issuing more specific guidance on the meaning of vague terms/provisions.

Taylor's study of interfaces for commercial communications of content creators is a good example. If a Code of Conduct, or soft-law recommendation based on a comparative overview, provides a specific solution, auditors could [or must for CCs] consider it in their auditing exercise (it does not become binding, to be clear). A good example of this is the draft guidance on Article 28. Once adopted, I would expect the audits of this provision to also include external benchmarks introduced by the guidance. Audits can then partly act as a privately funded (albeit imperfect) monitoring system for regulators. Unfortunately, in 2024, there was no useful guidance that auditors could use as a starting point.

In the recently adopted Opinion on the Code of Practice on Disinformation, the Commission is quite clear about how it sees its role (emphasis mine):

In practical terms, it follows from the above that following a positive assessment by the Commission and the Board under Article 45(4) of Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, the Code of Practice on Disinformation can serve as a significant and meaningful benchmark of DSA compliance for the providers of VLOPs and VLOSEs that adhere to and comply with its Commitments. This benchmark can play an important role in supporting the enforcement of the DSA in the area of disinformation, while the Commission retains its margin of discretion to decide in individual cases.

I will get back to these codes a bit later.

NGOs have been vocal about the fact that they felt they had not been consulted properly. I have argued before that wide consultation of stakeholders by VLOPSEs is helpful for society at large, but also benefits companies. If companies consult broadly and specifically, they can demonstrate for the purposes of Article 34 (procedural obligation to assess and document risks) that maybe some risks were not objectively known, or widely known at the time. The tendency of hindsight bias is all too human. So, let's hope things get better because it is a win-win.

New EC investigations

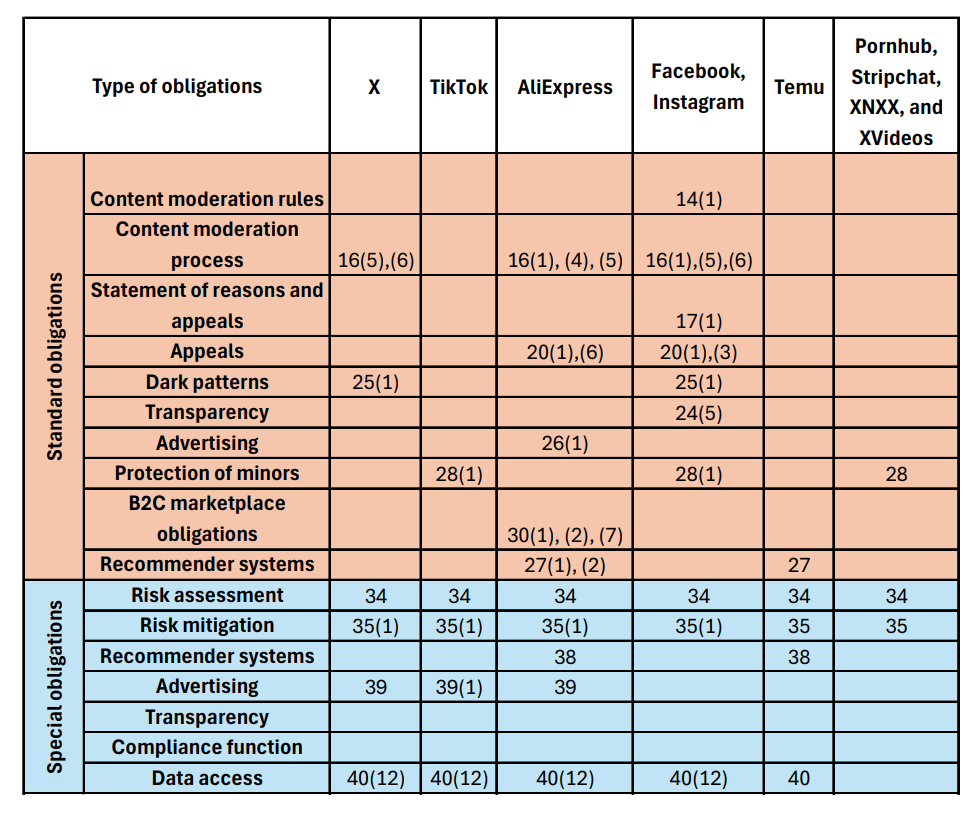

The table below presents the updated list of all EC investigations. The new investigations concern Temu and four adult sites (PornHub, Stripchat, XNXX and XVideos). The latter are focused protection of minors, including whether they introduced effective age verification technologies to exclude minors from their services.

XVideos has reacted publicly to the investigations by lashing out at the Commission. The company alleges double standards in the supervision of American and European VLOPs, calling the investigation a 'reputational hit campaign', and accuses the Commission of nothing less than censorship ('[t]he EU Commission is upholding its reputation for ideological rigidity and lack of pragmatism. It's also increasingly viewed as adopting totalitarian measures.'). Age verification is certainly something that should be rolled out with a lot of caution and humility, but equating it automatically with totalitarian techniques is simply far-fetched.

From the old investigations, there is less news, with one exception. AliExpress accepted commitments; however, they were still not published. The only available information is the EC's PR (see below). Since X's CEO famously declined commitments in July 2024, X should be heading for a decision on non-compliance (on Articles 25, 39 and 40(12)). Even though it is now one year later, we still haven't seen any such decision.

Based on PR, AliExpress's commitments are fairly elaborate. Most interestingly, they set up an independent monitoring system overseen by an Independent Trustee, who will oversee compliance in the following areas:

- The platform’s verification, monitoring and detection systems aiming at mitigating certain risks related to hidden links, its affiliate programme and products potentially affecting health and minors (likely Articles 34 and 35)

- The platform’s notice and action mechanism and the internal complaint handling system (Article 16 and 20)

- The transparency of AliExpress’ advertising and recommender systems (Articles 26, 27, 38, 39)

- The traceability of traders on AliExpress’ services (Article 30)

- Access to public data for researchers (Article 40(12))

For the period of five years, the Trustee will monitor compliance with these issues. The acceptance of commitments means that the Commission might fine the company on the sole basis of failing to uphold them. Once the document is published, I hope to share my observations on two points that seem rather interesting:

- AliExpress agreed to hire a third party to complement its monitoring of abuse on its system (hidden links, sale of fake prescription drugs, etc.)

- AliExpress agreed to apply an enhanced verification process for food supplement sellers and product listings concerning their authorisations and health claims.

- AliExpress agreed to limit the visibility of products intended for adults with functionalities such as automatically blurring images of adult products using AI-powered real-time scanning technology.

I especially wonder whether the Commission has dealt with the compliance of these commitments with Article 8, that is, the prohibition of general monitoring, and proportionality in general. To be sure, I can imagine their implementation that is compliant, but also some that are not. We will have to wait until the commitments are made public.

Moreover, the nature of commitments like these raises an important issue of third-party interests. Many commitments given by VLOPSEs are bound to affect third parties, who are never part of the original investigation. This begs the question of how to remedy potential overreach. Competition case law, such as the Groupe Canal+ case (Case C‑132/19 P, para 94 ff.) offers some clues even though it relates to contractual third-party interests.

ODS Bodies

The Commission's website now lists 35 trusted flaggers and 6 ODS bodies (although I remain unsure about Italian and Austrian ODS; if you know more, do let me know). ODS bodies have created the ODS Network to advocate for their interests. Recently, they reported that in January and March 2025, the four certified ODS bodies (ACE, User Rights, ADROIT and OPVT) received over 4,500 complaints. For the reasons I explain below, I suspect many were inadmissible, and many were resolved without any decision on the merits. However, the aggregate quarterly number is a good indicator of the uptake of the system by users, which still has a long way to go.

Based on my conversations, User Rights and ACE are currently preparing their reports about the use of their services. User Rights gave me an early glimpse into their preliminary numbers just to understand the trends. Based on what I have seen, it appears that:

a) inadmissibility rates (mostly due to the scope issues) are very high,

b) the main driver for self-correction of content moderation mistakes takes place at the point when platforms are notified about the case (i.e, at the very start of the procedure), and

c) decisions on merits are only a small subset of all the cases (but still with significant implementation rates).

While we should wait for the final data, the data so far seems to suggest that we need to do a better job promoting the ODS system. We can start by redesigning the atrocious (sorry!) EC website with the list of ODS bodies. Since this is the junction that all VLOPs are likely to refer to in their decisions to users, it should be user-friendly, including for minors. For instance, it could include an intuitive choice screen based on the scope of certifications, user-friendly explanations of the ODS process and more.

The next point concerns the reporting of error rates. The number of negative ODS decisions on merits (for platforms) is clearly a useless indicator of error rates. Platform reports according to Article 24(1)(a) might thus be less useful, unless they provide more contextual information. The true reversal rate should include initial reversals in response to the notification by ODS bodies. There is a hope that such information could be included in the annual reports of ODS bodies according to Article 21(4)(b) ('indicate the outcomes of the procedures brought before those bodies and the average time taken to resolve the disputes'). Once they are, the EC website could present such contextual information to users in the choice screen, so they can make fully informed decisions about which ODS to use.

Obviously, even this information does not capture the full error rate of the underlying system for a simple reason. Only a subset of people complain when they are aggrieved. While we can improve on this by teaching people how to do it, even with perfect information, not everyone will be bothered. That is just a fact (and the reason why risk assessments of Article 15(1)(e) compliance that rely on internal appeals as error rates are deeply flawed).

Other news is that ACE is expanding to cover Facebook/Instagram Pages and Groups, and another Meta product, Threads. User Rights now also covers Facebook and reviews French-language content by native speakers.

Finally, there is zero public information about the flow of payments to specific ODS bodies, but hopefully, transparency reports will tell us more. Based on my conversations, the payments are taking place (albeit not always in the ideal time frames).

DSA cases before the CJEU

In March, the General Court held its first hearing in a DSA dispute. In Zalando v Commission Case T-348/23 [2023], the Commission was defending its designation. The objections of Zalando related mostly to the scope of the DSA, including the question of neutrality, and the methodology for active user counting for the VLOP threshold (how to assess a hybrid marketplace; what is an acceptable way of counting and discounting users). Since I represented a consumer organisation, EISi, intervening on the side of the Commission, I will not be saying much at this point. I will only say that the hearing covered the issues quite exhaustively, and the majority of the questions of judges focused on the methodology for user counting.

In June, the General Court held two other hearings: Case T-367/23 Amazon EU v Commission [2023], and a joint hearing in two initial fee cases (Case T-55/24 Meta Platforms Ireland v Commission [2024] & Case T-58/24 Tiktok Technology v Commission [2024]). There are several new 2025 fee cases pending filed by Meta, TikTok, but also Google (Case T-88/25 Tiktok Technology v Commission [2025]; Case T-89/25 Meta Platforms Ireland v Commission [2025]; Case T-92/25 Google Ireland v Commission [2025]). The key problems are the common methodology used by the Commission for the fee calculation and the notion of a provider under the DSA. On the latter, I believe that effet utile requires a functional broad reading of the term along the lines of 'undertaking' in the DMA for a number of reasons, only one of which is fee calculation (e.g., establishment).

Although not strictly speaking a DSA issue, the Grand Chamber is also hearing another important case, Russmedia, Case C-492/23, that concerns the relationship between GDPR and the E-Commerce Directive's liability exemptions (now DSA's liability exemptions), and the prohibition of general monitoring. Advocate General Szpunar delivered a very thoughtful opinion that can be found here. TL;DR version: the hosting liability exemption must co-exist along with GDPR in harmony, which remains possible. The ruling can have an important impact on the limits of due diligence duties under the DSA's Chapter 3, but also on the liability exemptions in Chapter 2.

FIDE Report: How to Improve the DSA?

In May, I had the pleasure of acting as a general rapporteur for the DSA/DMA during the FIDE Congress. For those uninitiated, FIDE is the International Federation of European Law. Every two years, it organises a congress on several pre-selected topics of EU law. This year was presided over by Advocate General Szpunar and held in Katowice, Poland. 'The EU Digital Economy: DSA/DSA' was one of the sections which drew significant attendance from many leading experts, academics and judges from the Court of Justice of the European Union.

My FIDE report (PDF) is accompanied by an institutional report prepared by the Legal Service of the European Commission (Paul John Loewenthal, Cristina Sjödin, Folkert Wilman) and detailed national reports drafted by national rapporteurs. Together, we cover a lot of ground. My general report is mainly focused on a number of recommendations on how to improve and understand the DSA/DMA as a regulatory system. The national reports dive into the intricacies of the institutional set-up at the national level. While I am biased, I highly recommend it as your summer reading!

I say many things in the report, and there is no point in reiterating them all here. But I want to highlight two issues. The first one concerns the current worries about the potential watering down of the DSA/DMA standards due to trade negotiations between the US and EU. I argue that:

In my view, we must learn from the data protection law, where the Commission consistently negotiated weaker data transfer safeguards with the United States, than the ones that were expected by the Court of Justice of the Euro-pean Union. If we are serious about the empowerment of users in Europe, we must further insulate the DSA/DMA enforcement from the external and internal political pressures and create a dedicated and independent EU agency for this purpose.

I also respond to the US censorship criticism of the DSA that has been made fashionable by the second Trump administration. I summarise that:

Firstly, European legislatures have for a long time maintained different decisions about what speech must be prohibited. Such democratically ad-opted rules are not censorship only because they do not align with the case law of the US Supreme Court. Europe has its own tradition of freedom of expression. European Convention on Human Rights expects the European countries to outlaw expressions that cannot be outlawed in the United States, such as many forms of hate speech. In contrast, on matters of national security, the US case law can be seen as too willing to sacrifice freedom of expression from the EU perspective.

Secondly, as I explained, the DSA does not allow the European Commission to create new content rules, and thus it cannot ‘censor’ anything lawful. If it expects companies to remove unlawful content, it is because some legislature in the EU made a democratic decision that such content should be illegal in some circumstances.

Thirdly, nothing in the DSA expects companies to comply with such rules on illegality outside of the European Union. Companies are thus permitted to localise the compliance. Arguably, the de facto Brussels effect of the DSA is going to be weak.

Having said that, I do recognise that enforcement of Article 35 in particular can be an area for potential abuse. I address the debate about harmful but lawful, and the limits of the system on pages 55-60 of the FIDE report. My recommendation to improve the system is as follows:

The best way that the Commission could handle the censorship criticism would be to issue specific public guidance that provides the interpretation of Articles 14(4) and 35 that firmly rejects the existence of any competence to create new content rules by means of content-specific measures. Such guidance would draw a red line around the Commission’s exercise of the powers. It could be accompanied by a commitment to always explain how enforcement actions on the basis of Articles 14(4) and 35 comply with this red line. Going forward, such explicit safeguards should be explicitly enshrined in the DSA itself.

Admittedly, the DSA should have been more explicit in legislating this safeguard. However, the oversight can still be remedied by the Courts that would eventually review any enforcement decisions that the Commission makes.

I make a number of other operational suggestions, including suggestions for the upcoming review of the DSA/DMA. Please let me know what you think.

Data Access for Researchers

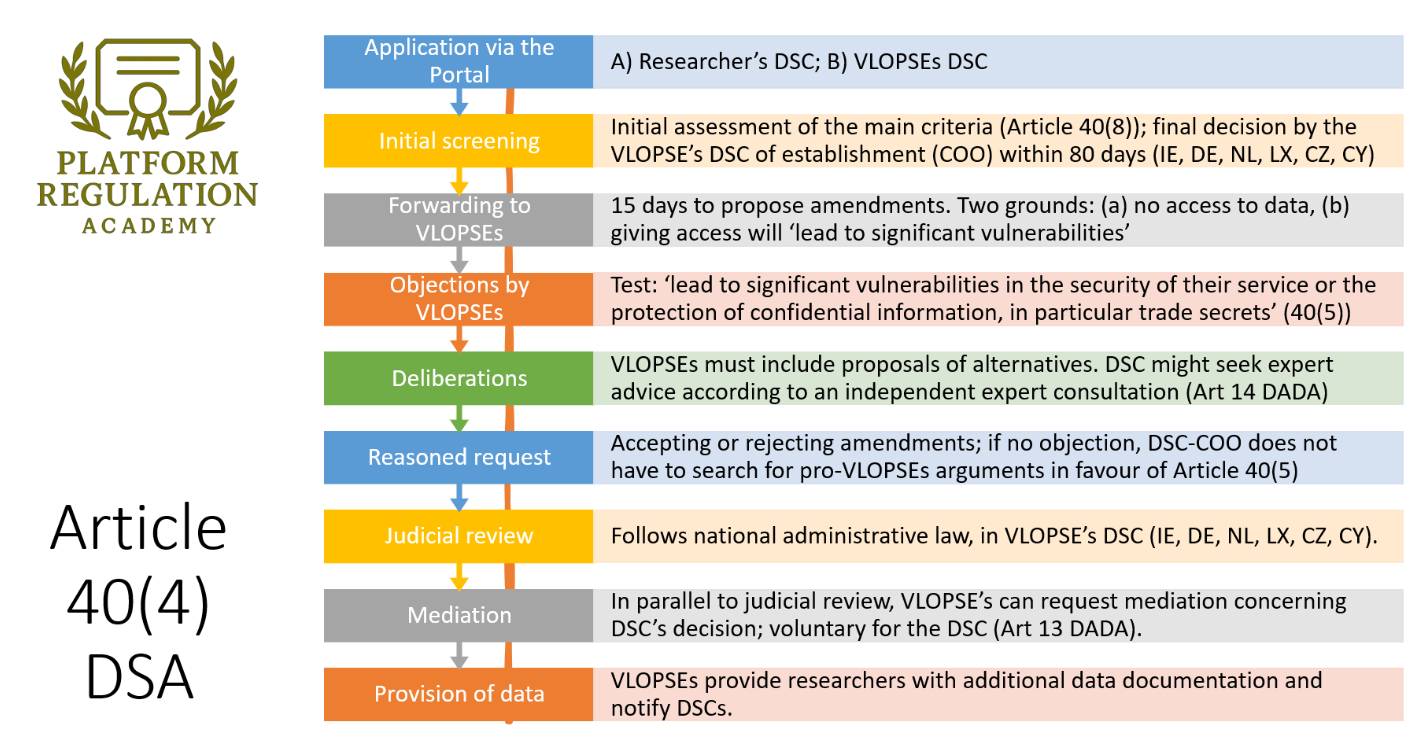

Several days ago, the Commission finally officially adopted the long-awaited Delegated Act on Data Access according to Article 40 DSA. This was the last roadblock for researchers before they could start applying for non-public data from VLOPs and VLOSEs. The delegated act clarified many issues, and the final version is clearly an improvement on the consulted draft.

Fantastic LK Seiling of DSA Collaboratory made everyone a favour by summarising how the final version differs from the draft. In short, the Commission has double-down on details about data catalogues (Article 6(4) and 6(5) of the DADA), prolongs the time limits for the DSC of establishment to decide (Articles 7(1)), further clarifies issues related to confidentiality, security and data protection (Articles 8(e)), 9(4), 10(3)), mediation (Article 13), renames independent advisory mechanism to independent expert consultation (Article 14), and further specifies how the data should be provided (Article 15(2) and (4)).

The resulting system looks something like this:

My biggest question concerns the potential judicial review of vetted researchers' access to data. If platforms start seeking judicial review of DSC decisions, this can seriously slow down the process for everyone. For researchers who are denied access, it might become difficult to seek judicial review, given that most VLOPSEs are based in Ireland, and the judicial review there can also be rather expensive.

I remain sceptical about the mediation process. VLOPSEs that are unhappy with the outcome must legally secure their objections by initiating parallel judicial review, usually within strict periods; otherwise, they risk that their requests for such mediation will be simply rejected by DSCs, while also missing the deadline and thus losing the possibility to seek judicial review. For a DSC, if a platform files a judicial review, it is unclear why they would continue in mediation. In other words, VLOPSEs might be interested in the mediation only when they see a slim chance of prevailing in court. This, in turn, begs the question of why DSCs would accept such mediation in the first place. But let's see what the practice brings.

I am currently considering developing a free online course for researchers seeking data access. My preliminary idea is to help the research community with the application process under the DSA's data access provision (Article 40 DSA). If you want to help by sharing your views, or send me difficult questions or good practices that I could reference, I would appreciate that. I am also thinking of creating a list of law firms that help researchers with legal difficulties during the process. If you practice in this area and want to help (pro bono or not), drop me a line. Especially if you are from a VLOPSE-land, that is Ireland, Germany, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Czechia or Cyprus.

If you are interested in reading more, here are some very good pieces of analysis I read on the topic recently:

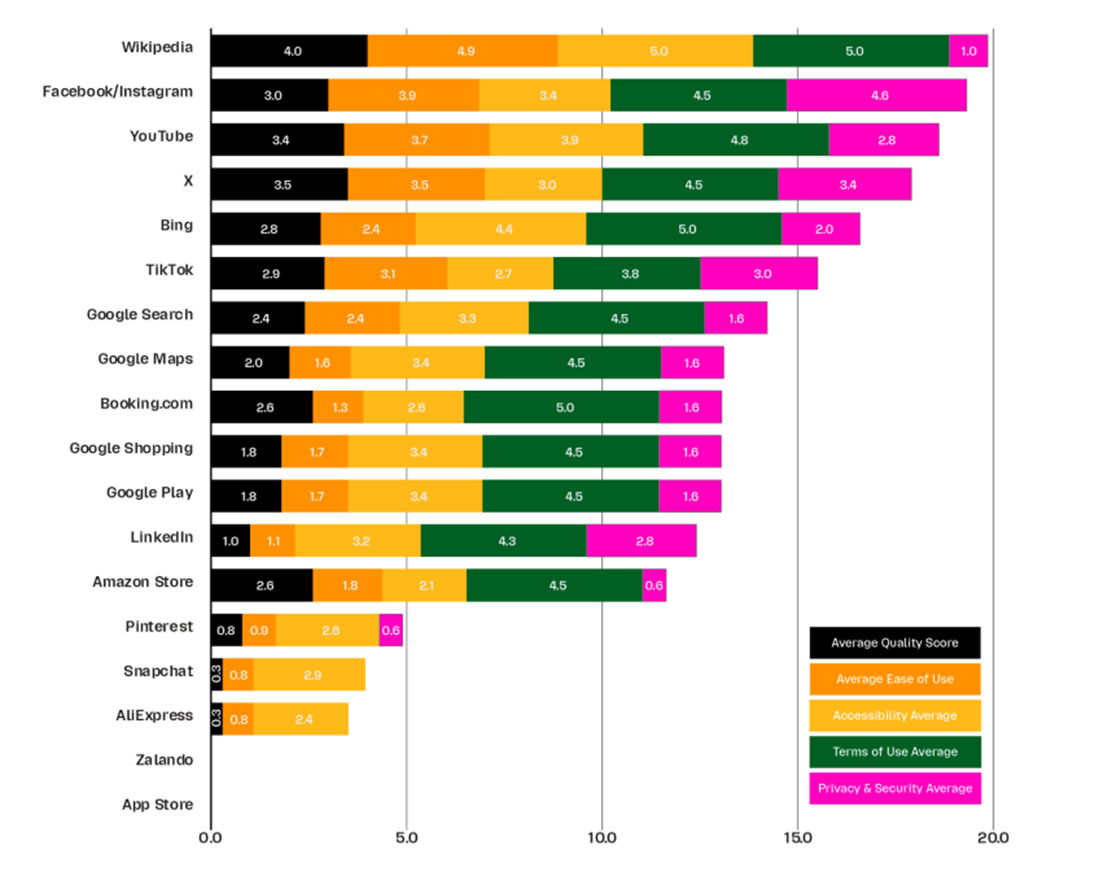

- Mozilla report on data access under Article 40(12) that rates different access regimes offered by VLOPSEs (see the picture below)

- Article 40: Collaboratory maintains a useful FAQ and reporting system for Article 40 data access requests

- Naomi Shiffman and Brandon Silverman, The Case for Transparency: How Social Media Platform Data Access Leads to Real-World Change

- CCG, Platform Transparency under the EU’s Digital Services Act: Opportunities and Challenges for the Global South

Protection of Minors

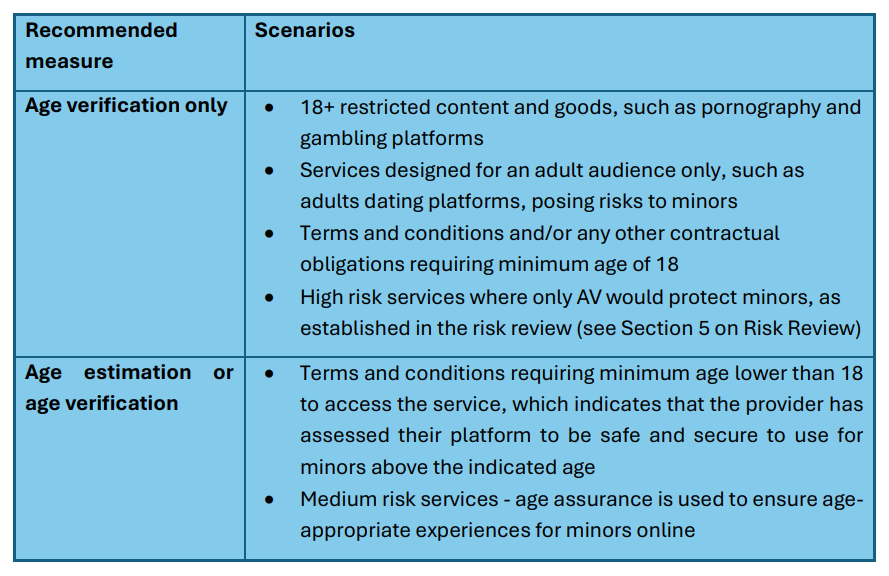

The Commission's draft guidance on the protection of minors did not disappoint. It really has transformational potential for the way we design digital services. I am generally very positive about it. It clearly borrows many ideas from the existing research and does not stay too general, but instead provides detailed recommendations. I have myself argued in the consultation that this guidance should be very different in style from the Electoral Integrity Guidance. The Commission delivered on this front. However, while I think the Commission got many things right (focus on design, level of detail, learning from research, etc.), there are some issues.

Firstly, the material scoping of the guidance seems to assume that if a service does not allow minors to enter, this must be because it carries content that minors should not see, or is made illegal for minors, such as adult content, gambling, or alcohol. However, platforms ban minors for all sorts of reasons (business focus: forum for young mothers, or elderly; liability or reputational issues, etc.). The guidance here seems to skip the requirement of 'accessible to minors', which is a qualitative criterion that must be met before the regulator can impose any obligations, including age verification. Thus, I do not think it is possible to assume that failure to put age verification for 18+ service makes the service within the scope of Article 28. This seems to follow from the following part:

This is further explained in Section 6.1.3 as follows: '[w]here the terms and conditions or any other contractual obligations of the service require a user to be 18 years or older to access the service, due to identified risks to minors, even if there is no formal age requirement established by law' (emphasis mine). This basically confirms that if a service states that it is above 18, regardless of the reason behind this, it would have to implement an age verification system. This is hardly in line with Article 28, which requires 'accessibility to minors' (Recital 71) before it can impose any obligations of such kind. Based on this guidance, a discussion forum for young mothers or the elderly that is limited to 18+ would require age verification, even if they barely have children showing up to read and contribute.

Secondly, while the Commission made a clear effort to focus on design-related obligations, such as settings, defaults, features or empowerment tools for minors, I still see some of the obligations as going beyond this mandate — especially in the part concerning recommender systems. One example of such content-specific measures is the following paragraph:

Implement measures to prevent a minor’s repeated exposure to content that could pose a risk to minors’ safety and security, particularly when encountered repeatedly, such as content promoting unrealistic beauty standards or dieting, content that glorifies or trivialises mental health issues, such as anxiety or depression, discriminatory content, illegal content and distressing content depicting violence or encouraging minors to engage in dangerous activities.

It is not clear if 'unrealistic beauty standards and dieting' is meant to be 'content harmful to minors' according to AVMSD, or if the category goes beyond. However, even if it is the so-called 'harmful content to minors' that has a legal basis, the basis does not extend to all online platforms. For instance, discussion forums are not video-sharing services (Article 1(1)(b)(aa) AVMSD [1]). In such cases, the provision is an attempt to regulate content specifically without a specific content law backing it up (contrast this with Article 9 AVMSD, which is much weaker for editorial content). As I have argued in my submission (and the book), Article 28 is an insufficient legal basis for such interventions. To be clear, I am not against such rules per se, but they must have a legal basis. It is one thing to change settings for all content, but quite another to target a specific type of lawful content.

[1] “video-sharing platform service” means a service as defined by Articles 56 and 57 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, where the principal purpose of the service or of a dissociable section thereof or an essential functionality of the service is devoted to providing programmes, user-generated videos, or both, to the general public, for which the video-sharing platform provider does not have editorial responsibility, in order to inform, entertain or educate, by means of electronic communications networks within the meaning of point (a) of Article 2 of Directive 2002/21/EC and the organisation of which is determined by the video-sharing platform provider, including by automatic means or algorithms in particular by displaying, tagging and sequencing.’

Upcoming Guidance

The Commission has announced a new consultation on Article 18 of the EMFA. This provision gives, at least in theory, extra procedural rights in addition to the DSA to media service providers. If you are interested, I gave a talk about this provision some time ago at ERA. The consultation will serve as input for the drafting process, as the Commission is aiming to prepare a recommendation on Article 18 EMFA. For the platform buffs, see also Sections 18-19 of the UK's OSA. Based on the minutes from the Board meetings, it also seems that there is another guidance on the way, one for Trusted Flaggers.

Codes of Conduct

The Commission has now also adopted two DSA codes of conduct. Codes of conduct are not legally binding and cannot serve as a basis for fines. As noted by Recital 104, compliance with them does not ‘in itself presume compliance with the DSA’. However, they inform compliance with the general risk management system laid down in Articles 34 and 34. Codes also have consequences for audits, because auditors must cover them along with the regular DSA obligations in their annual exercises (Article 37(1)(b)) and compliance officers must monitor them internally too (Article 41(3)(f)). They can also act as evidence of industry-wide benchmarks.

Here is how I explain the goal of the Codes in my book:

However, the DSA creates only a regulatory baseline. Its full harmonisation does not imply that the DSA rules impose the only golden standard of due diligence that cannot be exceeded in practice. The ‘DSA-plus’ measures are almost by definition expected to accompany the DSA in the years to come. To complement Big Tech’s open-ended risk management tasks, the DSA builds a separate co-regulatory arm to inform its scrutiny. For a regulator in such a dynamic and quickly changing landscape as digital services, there is little choice but to give some agency to providers to satisfy public policy goals. Different societal challenges have different levels of regulatory maturity, and regulators usually know less about potential solutions than the industry. The DSA architecture de facto reroutes society’s effort to co-regulation through a mixture of experimentation, industry-consensus building, and, eventually, standardisation.

The DSA remains fairly opaque on the question of who develops and adopts these codes. Based on my understanding, the current codes are everything but industry-driven (unlike in the Australian system). The Commission is in the driving seat, consults the industry, eventually adopts them by issuing opinions, and then offers them for signature to the industry. Each code is accompanied by an opinion of the Commission and the Board. This marks its adoption and publication on the website.

The above process has legal consequences. The formal adoption by the Commission, in my view, strengthens the point that the Codes can be interpreted and annulled by the CJEU in the preliminary reference procedure (Article 267 TFEU). CJEU long accepts that even non-binding instruments issued by institutions are within its jurisdiction (e.g., see Case C-911/19 Fédération bancaire française (FBF), para 53, and the discussion of this in my book, pages 453-456). However, a direct legal challenge to Codes is much trickier, as it is not clear if they could be regarded as 'challengeable acts' for the purposes of Article 263 TFEU. In the book, I speculate that VLOPs might have some chance, but how much depends on the content of the codes.

The above points are not only my musings, as it is not too difficult to imagine Codes that undermine third-party interests.

The hate speech code of conduct has been renamed The Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online + (Code text, EC Opinion, Board Opinion). The code's focus is only on illegal hate speech, that is, speech that is made illegal by national law as hate speech, mostly to implement the EU Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA [2008]. Thus, the scope is very clearly about illegal content only, as understood by the DSA. The core obligation is as follows:

The Signatories commit to review the majority (at least 50%) of notices received under Articles 16 and 22 of the DSA from Monitoring Reporters within 24 hours. Signatories will apply their best efforts to go beyond this target and aim for two-third (at least 67%) of those notices subject to Annex 1 [Methodology / Safeguards].

Thus, the core requirement under the code remains to demonstrate the speedy removal of illegal hate speech. The compliance is tested by a network of monitoring reports in each country. The only notices that count are those submitted as Article 16 [illegal content] / 22 [illegal content by trusted flaggers] notices. So far, so good.

The problem with this target is that it does not measure the accuracy of platform decisions symmetrically. What do I mean? The above commitment in Article 2.3 HCC+ is subject to Annexe 1, which introduces a very weak safeguard against only one type of mistake. When providers dispute a notification, and the disagreement between the Monitoring Reporter and platforms persists, this can lead to the disqualification of the Monitoring Reporter (70% unresolved Dispute Cases for two monitoring rounds - see Article 5.3 of Annexe 1). Arguably, this is very generous. Any trusted flagger should be stripped of their certification, even if half of such cases are objectively unfounded (not all MRs are trusted flaggers, to be sure, but the role is similar here).

The problem is that if a platform simply over-removes too much content by making the opposite type of mistakes, e.g., not properly considering the context, and removing something that is not illegal hate speech, this never becomes a Disputed Case. The only thing that the Code foresees for such a case is to require providers to report on the number of appeals by users (Annexe 2, Article 2.6.c). In other words, while under-removal is subject to transparency and some lenient sanctions, over-removal is only subject to a generic transparency safeguard that fully depends on users taking action and complaining first, and the provider again doing a good job re-evaluating their appeals. One would expect that the Code could include better testing of the underlying tools and processes for both types of mistakes, for instance, fleshing out Article 15(1)(e) (false positives and negatives alike; Annexe 2, Article 2.7 is too vague). This seems to be an issue. Have I missed anything? Do let me know.

Another noteworthy obligation is that platforms must report on '[a]ny additional details on relevant information or metrics related to hate speech on the Signatories’ platforms, for example, where available, on the role of recommender systems and the % of illegal hate speech that was removed before accumulating any views' (Annexe 2, Article 2.6.e).

The second, more complex code of conduct relates to disinformation. The Code of Practice on Disinformation (Code text, EC Opinion, Board Opinion) took effect on 1.7.2025. I wish I had more time to delve into it, but let me say just a few words are it is very complex. The code covers the following areas:

- Demonetisation: cutting financial incentives for disinformation

- disinformation source should not earn advertising revenues

- Transparency of political advertising

- e.g., labelling of ads, searchable ad libraries

- Ensuring the integrity of services

- e.g., cross-service agreed dealing with unpermitted activities, including fake accounts, bot-driven amplification, impersonation, malicious deep fakes.

- Empowering users

- media literacy and more context

- Empowering researchers

- accesss to data

- Empowering the fact-checking community

- consitent coverage and fair remuneration

- Transparency Centre and Task-force

- Strengthened Monitoring framework

The CoPD has been signed by several industry players, including Meta, Microsoft, Google and TikTok (see here), but Democracy Reporting International shows that there has been a significant withdrawal of commitments among signatories.

I certainly welcome specific empowerment duties that the Code introduces. The Code aims to provide a lot of analytical data that can be of help. It also fleshes out or complements some of the DSA obligations. However, I have real difficulties understanding and potentially agreeing with certain provisions of the Code.

I have tried to understand the definitional part of the Code for quite some time. But every time I ask insiders, I receive a different answer. Some people say that the Code has uniform definitions, pointing to the Code's footnotes that define it by citing the European Democracy Action Plan (EDAP).

It is important to distinguish between different phenomena that are commonly referred to as ‘disinformation’ to allow for the design of appropriate policy responses:

- misinformation is false or misleading content shared without harmful intent though the effects can still be harmful, e.g. when people share false information with friends and family in good faith;

- disinformation is false or misleading content that is spread with an intention to deceive or secure economic or political gain and which may cause public harm;

- information influence operation refers to coordinated efforts by either domestic or foreign actors to influence a target audience using a range of deceptive means, including suppressing independent information sources in combination with disinformation; and

- foreign interference in the information space, often carried out as part of a broader hybrid operation, can be understood as coercive and deceptive efforts to disrupt the free formation and expression of individuals’ political will by a foreign state actor or its agents

Other insiders say that these are only scoping definitions, and it remains for platforms to define what they consider to fall under such policies. It seems that the Commission itself points to Measure 18.2 in its opinion to say that 'signatories' are those who 'develop and enforce' such policies (EC Opinion, page 7). But I could be over-reading it, and there is no other discussion of this point.

Two conceptions have completely different consequences. While the first one undoubtedly amounts to a regulation of content (ala 'show less content defined as XY'), the latter could maybe avoid it. The former, in my view, lacks a legal basis in the DSA. The latter means that whatever platforms do to implement parts of the code is not comparable because some can define disinformation as apples and others as oranges; while they are both fruits, the analytical insights (or policy outcomes) are greatly diminished by this. One additional argument I have heard is that maybe Code's obligations, such as demonetisation, regulate content, but they also, in these areas, they go beyond the DSA, and thus could not be enforced on its basis. That could be so, but then is it right to connect them with the DSA-relevant legal effects, such as audits?

I am seriously puzzled by this and welcome any clarifications or observations from those who know more.

Both Codes are accompanied by opinions of the Commission and Board. The Commission's opinion reads very much like the Legal Service's opinion on the matter. I have personally found both opinions somewhat vague. The Hate Speech Opinion barely looks at the question of over-blocking in the main text, even though it is the key issue. It is not key because I think so, but because comparable mandates were invalidated in France by the Constitutional Council due to concerns of over-blocking. Similarly, CJEU accepted the constitutionality of copyright upload filters only subject to safeguards against over-blocking (C-401/19, Poland v Parliament and Council). Though the Opinion does include at least one useful reference to errors in paragraph 49, where it says:

the Commission also encourages signatories to provide more detailed information about the moderation path for hate speech notices when implementing the commitments made in the Code. An important element in that regard would be the inclusion of information about the internal classification of hate speech (for example, the grounds of hate speech such as race, ethnicity, religion, gender identity or sexual orientation), the training of classifiers for systems for the detection of hate speech in all official EU languages, the accuracy of classifiers (such as error rates), the number of appeals requested by users and the error rate of human and automatic content moderation decisions.

The Commission's Opinion on Disinformation Code of Practice pays more attention to freedom of expression (e.g., para 22-24), but does not address the above definitional issue, or deal with questions of the legal basis for some of the content-specific restrictions.

In both cases, the Commission looks at the four issues derived from Article 45 (see below). However, its analysis is not a typical analysis of the proportionality of an interference. Instead, the part about contribution to the DSA objectives looks at complementarity with the DSA and stated goals, and the part about third-party interests mostly looks at stakeholder involvement in the process. At least, that was my impression. The opinions do not delve into complex questions of whether an interference with rights that might be affected is proportionate, and whether they are subject to sufficient safeguards. As a result, no imposed commitments are examined, and more importantly, typical safeguards, such as again over-blocking, or concerning the principle of legality, are discussed.

Pursuant to Article 45(4) of Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, the Commission’s assessment of a particular code of conduct aims at verifying whether the conditions set out in Article 45(1) and (3) of that Regulation are fulfilled, that is whether:

(a) the code contributes to the proper application of the Regulation, taking into account in particular the specific challenges of tackling different types of illegal content and systemic risks, in accordance with Union law in particular on competition and the protection of personal data (Article 45(1));

(b) the code clearly sets out its specific objectives (Article 45(3));

(c) the code contains key performance indicators to measure the achievement of those objectives (Article 45(3)); and

(d) the code takes due account of the needs and interests of all interested parties, and in particular citizens, at Union level (Article 45(3)).

Council of Europe Recommendation on Online Safety and User Empowerment

The Council of Europe has now released the Draft Council of Europe Recommendation on Online Safety and User Empowerment for public comment (deadline: 8.8.2025). For several months now, I have been involved in drafting this recommendation as a rapporteur along with Peter Noorlander, together with other members of our expert committee and CoE staff. Our goal is to look at laws like EU DSA and UK OSA, extract the essential framing and obligations to help other countries develop their own model of platform regulation that is grounded in freedom of expression, the rule of law, and which empowers users and content creators. Do let us know how we are doing by contributing to the consultation.

Overview of National cases

- A Dutch case on shadow banning against X/Twitter (here)

- Articles 14 and 17 DSA [resolved]

- A German pre-trial enforcement against Temu and Etsy (here)

- Article 31 DSA [decided]

- A German case on dark patterns against Eventim (here)

- Recognising a broad carve-out in Article 25(2) DSA but using it to read the consumer acquis in light of the DSA [decided]

- A German case on data access against X/Twitter (here)

- Recognising the direct enforceability of Article 40(12) DSA and special jurisdiction according to Brussels I Recast in the place of damage [decided]

- An Irish case against Online Safety Code by X/Twitter (here; here)

- Pre-emption by full harmonisation of Article 28 [pending]

- TikTok and Meta cases against AGCOM decisions in consumer law [pending]

- Pre-emption and exclusive competence of the EC

That's all, folks. Enjoy your summer!

PS: If you have colleagues who are considering taking the DSA Specialist Masterclass, do let them know that there is a special summer offer: 30 % off until 31.8.2025.